Several years ago both

Google

and

Facebook

ran a large advertisement campaign in Dutch newspapers assuring us

that our data was safe with them. What the campaign also

apparently tried to achieve was to reframe privacy as “if you give us

all your data, we will keep it private.” This is hugely problematic,

as privacy does not mean that Google or Facebook keep our data

private. Privacy means that we ourselves can do so. Adding insult to

injury is the fact that companies like Google and Facebook are

actively subverting our abilities and efforts to do so.

Several years ago both

Google

and

Facebook

ran a large advertisement campaign in Dutch newspapers assuring us

that our data was safe with them. What the campaign also

apparently tried to achieve was to reframe privacy as “if you give us

all your data, we will keep it private.” This is hugely problematic,

as privacy does not mean that Google or Facebook keep our data

private. Privacy means that we ourselves can do so. Adding insult to

injury is the fact that companies like Google and Facebook are

actively subverting our abilities and efforts to do so.

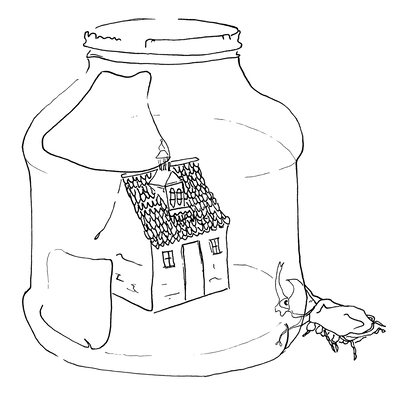

(This is the sixth myth discussed in my book Privacy Is Hard and Seven Other Myths. Achieving Privacy through Careful Design, that will appear October 5, 2021 at MIT Press. The image is courtesy of Gea Smidt.)

A strong form of privacy protection is achieved when processing personal data locally, on the device of the user. This essentially shields the personal data from the service provider. Whether the service can be implemented in a completely local fashion depends on the service of course. But in many cases this is certainly possible. This is the case for fitness apps for example, that track your daily fitness performance (as long as you do not want to share your runs with others), or menstruation apps that track your menstrual cycle. The problem is that many services are by default implemented in such a way that all data is synced in the cloud by default, whether you like it or not. And that, more often than not, the data in those clouds is not as safe as they should be.

Even location based services, for example map-like apps that show you restaurants or other points of interest in your area, can be implemented in a much more privacy friendly fashion than the current method of tracking your exact location and using server-based profiling to return relevant matches. A more privacy aware approach would only share your coarse location with the service provider (e.g. your location rounded to an area of a few square kilometres in size), while your device would refine the results returned by the service provider based on your exact location and interests.

Also when sharing data is part of the core functionality of the service, it is not necessary to store all the data on a single cloud server under the control of the service provider. Decentralised or even completely distributed architectures are certainly possible. One example is Mastodon, a decentralised Twitter alternative, where users choose a particular ‘instance’ to store their messages on. More general approaches are so called Personal Data Stores (like Solid), that aim to replace a single central database with customer data or user accounts at a single company with a distributed federation of nodes that store the same data. Users select the node to store the data on, and then grant many different companies and organisations specific rights to access this data. These companies and organisations retrieve the necessary data from the storage node each time they need it. The benefit is fourfold: users only need to update personal once (for example a change of address when they move), users have immediate control over access to their data, companies are more certain that the data they retrieve is up to date, and companies no longer need to store and protect the data themselves.

A word of warning is in order here. All approaches that propose to store all personal data locally throw all responsibility for their privacy back at the feet of the users. This assumes that people always are willing and able to make the right decisions. And this is not always the case. There is also a more fundamental limit to the protection offered by processing data locally. By moving intelligence to our own devices this line of defence breaks: though there is no central place where information about our personal details resides, the system as whole (i.e., the system comprised of all our own devices as well) still knows about us, and it predicts, judges, and nudges us. In fact, the excessive power companies like Google and Facebook now wield cannot be curtailed by only addressing their privacy violations. How they obtained that power and, more importantly, how it can be reduced is a fundamental question left unanswered by studying surveillance capitalism only through the lens of surveillance. Perhaps we need to shift our attention and focus on the underlying capitalist premise instead. In other words: “It’s the business model, stupid.”

(For all other posts related to my book see here)