Traditionally a distinction is made between data and metadata,

separating the actual content of a communication (e.g., a letter, a

phone conversation) from the technical data necessary to establish the

connection between the sender and the recipient (e.g., an address, or

a phone number). Unlike its metadata, the data itself is often

considered private and offered stronger protection: the secrecy of

correspondence is enshrined in the constitution of many countries. But

shouldn’t metadata be given similar protections? Is it really ‘merely’

metadata?

Traditionally a distinction is made between data and metadata,

separating the actual content of a communication (e.g., a letter, a

phone conversation) from the technical data necessary to establish the

connection between the sender and the recipient (e.g., an address, or

a phone number). Unlike its metadata, the data itself is often

considered private and offered stronger protection: the secrecy of

correspondence is enshrined in the constitution of many countries. But

shouldn’t metadata be given similar protections? Is it really ‘merely’

metadata?

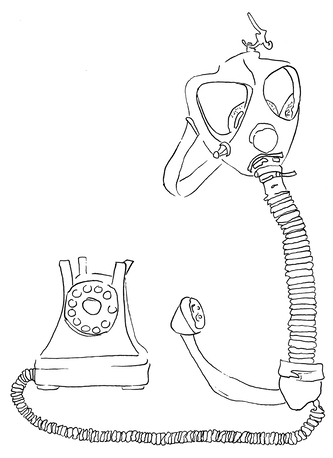

(This is the fourth myth discussed in my book Privacy Is Hard and Seven Other Myths. Achieving Privacy through Careful Design, that will appear October 5, 2021 at MIT Press. The image is courtesy of Gea Smidt.)

To be honest, it no longer is (and perhaps it never was). Because of their leaky design (and I have much more to say about that in the book itself), computers, smartphones and networks radiate all kinds of metadata. Each small piece of metadata (a phone number, an IP address, the time of a call, your current location) is perhaps innocuous. But these crumbs of data are each linked to a particular device, that belongs to a particular person. These links allow these crumbs of data to be combined to piece together a detailed profile of this person. Their name may remain unknown, but their shopping habits, daily routines, friends or family may be observed, and certain preferences, desires, may be inferred.

One could even consider metadata to be more sensitive than the actual data it pertains to, for several reasons. First of all, the data itself is often knowingly and explicitly shared: when filling in a form, uploading a picture in the cloud, or sharing it on Facebook, we know who we send the form, and know who we share the picture with (although not everybody may be aware of the access Facebook and its partners have to the content you share). But the metadata is shared without us being explicitly aware of this: the cookies collected when filling in the form, the IP address of our computer we use to fill in the form, the time and date we fill in the form, how long it takes us to fill in the form, how often we moved our mouse while filling in the form, etc. This data is collected surreptitiously, and we have no control over it. Secondly, metadata is much more structured than the original data itself: dates, locations, IP addresses are easily analysed and combined. It is much harder (though certainly not impossible) to derive the same information from a spoken conversation or the contents of an email. Finally, the term metadata really disguises its true significance and risk. A better term would be behavioural data. Because that is really what metadata is all about: data about our behaviour, what we do, where and when. And through our behaviour, what we do, we subconsciously reveal a lot more about our deepest desires and needs than what we explicitly divulge when talking our writing.

Because of the leaky design of our computers, smartphones and networks, it is much harder to prevent the collection of metadata. A radical redesign of their architecture (which, as far as computers and networks are concerned do not fundamentally differ from their initial designs, created fifty to eighty years ago) is urgently needed. In the meantime, there are a limited set of options available.

Regarding the computers we use and especially the smartphones we carry with us all the time, it is important to review their default settings and severely limit the permissions we give to the apps we use: block cookies and trackers, do not share your location, block access to your contacts, etc. Manufacturers and service providers should make these settings the default.

Networking is more difficult: virtual private networks shield your IP address from the websites you visit, but allow the VPN provider to profile you. In other words, you need to trust the VPN provider, and this trust may not be warranted. A much better approach is to use a technique called mixing. The essence if the idea is that privacy is protected when you hide in the crowd. In the context of networking this means your network traffic is processed by several nodes in sequence, each mixing your network packets with those of others, creating (as far as any outsider is concerned) a tangled mess of network packets that can no longer be traced to their source. The most well known system offering this strong level of privacy protection is the Tor network. Recently Apple announced a similar, but slightly weaker, service called Private Relay, that looks to bring mix networking to the masses.

These are good developments, but more is needed. In the current situation, any service relying on internet connectivity can only promise not to track people based on the IP address they use. For this reason I would be very much in favour to at least incorporate sender anonymity (as offered by such mixing networks) into the protocols of the internet itself, and make it the default. With that, many web services suddenly become much less privacy invasive, and new privacy friendly services become much easier to deploy.

(For all other posts related to my book see here)